Analysis of Feed Grade Chicken Litter

It is important that the beef industry avoid a controversy over the healthfulness of beef. Broiler litter has been used as feed for decades in all areas of the country without any recorded harmful effects on humans who have consumed the products from these animals. In addition, in Alabama, litter is most commonly fed to brood cows and stocker cattle that are not usually marketed as slaughter beef. Very little if any litter is in the diets of finished cattle fed for slaughter (although, allowing a 15-day withdrawal period from feeding litter before slaughter, such a diet would be considered safe). So the possibility of any human health hazard is remote.

In sum, the use of broiler litter as a cattle feed offers three primary advantages:

In 1967, when the FDA issued a policy statement that discouraged the feeding of litter and other types of animal wastes, there was relatively little knowledge available on feeding broiler litter. In 1980, after extensive testing by researchers at universities and USDA facilities, the FDA rescinded its earlier policy statement and announced that the regulation of litter should be the responsibility of the state departments of agriculture. At present at least 22 states have regulations pertaining to the marketing of litter and other animal wastes as feed ingredients.

Presently, no federal laws or regulations control the sale or use of broiler litter as a feed ingredient. Also, no state laws specifically regulate the feeding of animal waste and other by-products. But, several states have regulations that govern the sale through commercial markets of these products intended for sale as a feed ingredient. The Alabama Board of Agriculture and Industries adopted regulations under the Commercial Feed Law to deal with only commercial transactions of processed animal waste. These regulations do not address private use or exchange of broiler litter or other animal waste.

Processed broiler litter offered for sale in commercial channels as a feed ingredient must meet certain quality standards. The regulations governing animal-waste feed were adopted by the Board of Agriculture and Industries and went into effect January 1, 1977. Those regulations are listed under Agricultural Chemistry Regulation No. 9. If animal waste contains drugs or drug residues, it must carry a label that reads "WARNING: This product contains drug residues; do not use within 15 days of slaughter." This warning should also be observed by any farm feeder of broiler litter.

The beef producer, regardless of government regulation of the feedstuffs used, has the responsibility of selling a wholesome animal that is free from drugs and toxic substances. To minimize risks from drug residues in the tissues of beef cattle that are fed litter, all litter feeding should be discontinued 15 days before the animals are marketed for slaughter. Litter should not be fed to lactating dairy cows, because there is no opportunity for a withdrawal period to ensure the elimination of residues from milk. Because of the sensitivity of sheep to copper, litter containing high concentrations of copper should not be fed to these animals. These safety precautions are generally sufficient to eliminate most health risks associated with drug residues that may be associated with broiler litter.

For further information on regulations governing the commercial sale of broiler litter, contact the Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries. As stated previously, these regulations apply only to broiler litter offered for commercial sale.

Nutritional Value of Broiler Litter

The bedding materials used in broiler houses in Alabama are wood shavings, sawdust, peanut hulls, and some shredded paper products. Poultry house owners use these products in varying amounts for the initial bedding and sometimes as additional bedding after each batch of birds. The bedding material alone is a low-quality feed ingredient. However, with the addition of waste feed, feathers, and excrement from the birds, the nutrient quality of the litter improves. Litter from under the feed lines in a poultry house should be the highest quality due to the addition of spilled feed.

The kind of bedding material used in a broiler house has little effect on the quality of the litter when it is used for feeding cattle. Because the amount of bedding used and the number of batches of birds housed on the litter are not standardized or regulated, litter quality can vary considerably from one producer to another. Other factors such as broiler house management, the method of litter removal, the frequency in which bedding from houses is removed, and moisture content can add to the variation in litter composition and quality. The average nutrient content of 106 samples of broiler litter collected from across Alabama is shown in Table 1.

Moisture. The amount of moisture in broiler litter is determined by the management of ventilation and watering systems in the broiler house. The moisture content of the litter does not vary significantly between fresh litter and litter stacked for 6 months.

Though moisture content is not an important measure of nutrient value, it will determine the physical quality of the feed. If the moisture content is 25 percent or more, a feed mix will not flow easily through an auger.

However, if the broiler litter is 12 percent moisture or less, the ration may be dusty and less palatable to the cows. Some beef producers see an increase in feed consumption when water is added to extremely dry mixtures of litter and grain just prior to feeding.

TDN. The Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN) figure is calculated from crude protein and crude fiber values. The energy value of broiler litter is fairly low in comparison to grain. However, litter that has a calculated value of 50 percent TDN is comparable to average- quality hay. Litter could be a valuable source of energy for both stocker cattle and brood cows.

Crude Protein. The average crude protein level of the samples analyzed was 24.9 percent. More than 40 percent of the crude protein in litter can be in the form of nonprotein nitrogen. The nonprotein nitrogen is mostly uric acid that is excreted by poultry. Young ruminants do not utilize non-protein nitrogen as readily as more mature beef cattle. So, for best performance, feed broiler litter to beef cattle weighing more than 400 pounds.

Bound Nitrogen. When feed ingredients overheat, the nitrogen becomes insoluble (bound), and cattle can digest it less easily. The bound nitrogen in the litter samples analyzed in this study averaged 15 percent of the total nitrogen. In litter that showed signs of overheating, more than 50 percent of the total nitrogen was bound nitrogen.

Studies have shown that as the amount of bound nitrogen increases, the dry-matter digestibility decreases. Thus, overheating significantly reduces the feeding value of the litter. Methods for managing the temperature of stored litter are discussed in the section on processing and storing broiler litter.

Crude Fiber. Crude fiber composed an average of 23.6 percent of the samples analyzed. The fiber comes mainly from chicken bedding materials such as wood shavings, sawdust, and peanut hulls. Bedding usually consists of finely ground, short fiber materials.

The fiber in litter cannot effectively meet the ruminant's need for fiber, because cattle also need long roughage to maintain their digestive systems properly. Cattle fed litter will naturally crave and readily consume long roughage. Even though the fiber content of litter is high, it is recommended that additional fiber be fed in the form of long hay or other roughage at a level of 1⁄2 pound per 100 pounds of body weight.

Minerals. Broiler litter is an excellent source of minerals. In fact, brood cows fed a diet of 80 percent litter and 20 percent grain will consume five times more calcium, phosphorus, and potassium than required.

The excess minerals are not a problem except under specific conditions. The 2 percent calcium level, in the presence of an imbalance of other minerals, can cause milk fever in beef cows at calving. This risk can be reduced by removing brood cows from a litter ration before calving or by providing at least half of their feed as hay or other roughage. It is not known exactly how many days before calving a cow should be removed from litter. However, based on milk fever studies with dairy cattle, 30 days should be adequate. Milk fever may be a problem with a small number of cows after parturition. Therefore, brood cows consuming broiler litter at calving should be checked often.

The micro-minerals, copper, iron, and magnesium are also present in larger amounts compared to conventional feed ingredients. Copper, for example, is usually not fed at more than 150 ppm in beef cattle diets. Higher levels can cause copper toxicity. A brood cow herd fed broiler litter during the 120-day winter feeding period could receive more than 600 ppm of copper. The excess copper will build up in the liver tissue, but it is usually not harmful. The copper tissue level will usually return to normal after the summer grazing period, when no broiler litter is consumed.

Young stocker cattle fed a growing ration of 50 percent litter and 50 percent grain will consume copper in excess of 225 ppm. Young cattle, especially those compromised by disease, can tolerate this high level of copper for only 180 to 200 days. Feeding stockers on broiler litter for less than 180 days will significantly reduce copper toxicity problems.

Ash. Ash in litter is made up of minerals from feed, broiler excrement, bedding material, and soil. Ash content is one of the important measures of the quality of litter. The samples analyzed contained an average of 24.7 percent ash. Ash contents of more than 28 percent are too high and should not be fed to beef cattle. This can interfere with rumen digestion and mineral utilization.

Calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and trace minerals make up about 12 percent of the ash in broiler litter; the remaining ash is soil. Care should be taken to keep the ash content, especially the soil percentage, as low as possible if the litter is to be used for cattle feed. Most soil is incorporated into litter during removal from the broiler house and loading on trucks for transportation. With modern equipment, this is less of a concern today than it was in the past.

Processing and Storing Broiler Litter

Broiler litter, like any other feed ingredient, has potential hazards associated with its use. It is not uncommon for litter to contain some broken metal from the normal equipment breakdowns in a poultry house. This can lead to hardware disease if these items are ingested. Many common feed ingredients have risks associated with pesticide residues, mycotoxins such as aflatoxin, and even nitrate toxicity. Broiler litter has potential hazards associated with pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella, and residues from medicated poultry rations, such as antibiotics, coccidiostats, copper, and arsenic. All litter, regardless of its source, should be processed to eliminate pathogenic organisms.

Composting of normal poultry farm mortality is an approved and widely utilized method of dead bird disposal. Although this method might acceptably solve the problem of dead bird disposal, litter used in this way should not be used as a feed source for beef cattle. It is important to note that compost is the term most poultry growers associate with the finished product from dead bird disposal. The potential for disease transmission to the cattle has not been determined, and until research is complete, it is recommended that such litter not be used as a feed ingredient.

Processing of broiler litter as a feed ingredient can be accomplished by any one of several methods:

- Litter can be mixed with other feed ingredients and ensiled to encourage acid production that is common with corn or sorghum silage. When ensiling litter with corn or sorghum silage, add litter at 20 to 30 percent of the dry matter of the silage crop.

- Litter can be directly acidified to achieve essentially the same effect.

- Litter can be heat-treated as would occur during mechanical drying or pelleting of feeds.

- The most economical and by far the most practical method of processing litter is deep stacking. A temperature of 130 degrees F or higher should occur in the stack within 5 days. To ensure the elimination of Salmonella and other potential pathogens, the litter should be deep-stacked for at least 20 days. Studies have demonstrated that pathogenic bacteria (intentionally added to litter at levels higher than encountered in infected litter) were killed when litter was deep-stacked for 5 days. Longer stacking times are recommended to ensure a good margin of safety from pathogens. Modern ventilation systems in newer poultry houses can lead to lower moisture levels in litter compared to older houses. Low moisture can prevent heating to the 130-degree threshold, so it is critical that producers monitor the temperature during the deep stacking process. It may be necessary to add water to achieve proper heating.

In addition to the heat generated in stacked litter, ammonia resulting from the degradation of uric acid and urea, which are common nitrogen compounds in litter, also kills pathogenic organisms. At 140 degrees F, bacteria such as Salmonella, tubercule bacilli (associated with avian and bovine tuberculosis), and pathogens excreted with feces are killed within an hour. There is essentially no risk involved with transmitting diseases through the feeding of litter if the litter has been deep stacked for a period of 20 days or more, and the stack has reached an internal temperature of 130 degrees F or more.

Antibiotics fed to broiler chickens are not a problem when the litter is fed to beef cattle. Many of the antibiotics are degraded by microorganisms present in the litter as it is processed. Furthermore, essentially all the antibiotics approved for chickens are also approved for cattle.

Mycotoxins such as aflatoxin are not a cause for concern when feeding litter to cattle. Molds that produce mycotoxins do not grow well in litter because it is alkaline, because it releases ammonia that is toxic to molds, and because the growth of molds is limited to surfaces exposed to air. Deep-stack processing of litter helps to curtail mold growth.

Broiler litter is usually handled in bulk and transported in fairly large amounts. Thus, some beef producers store litter in 100- to 300-ton stacks. With proper storage there is very little loss in quality, even when litter is stored for more than 5 years. However, some precautions must be taken to ensure a good-quality litter at feeding time.

Heat is the one thing that reduces the quality of broiler litter in the stack. Excessive heating reduces the digestibility of the dry matter in the litter. Fresh stacked litter develops heat spontaneously. Trials have been conducted using a number of chemical additives such as urea or acid, as well as other procedures, to limit the heating of stacked litter.

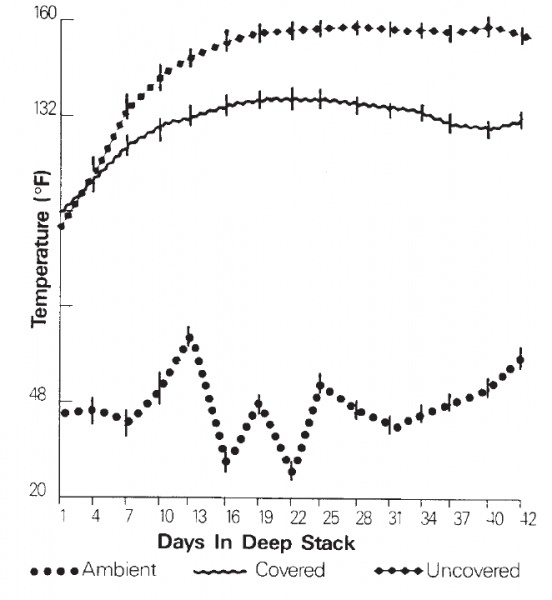

Figure 1. Temperature profile for little, measured 4 feet from top of stack

Excessive heating (more than 140 degrees F) can be controlled by limiting the moisture content of the litter to less than 25 percent and by limiting the litter's exposure to air. Some producers use farm tractors to exclude oxygen when packing broiler litter. This process will reduce overheating, but it is also expensive. Storing broiler litter in an upright silo has been shown to be an excellent storage procedure. However, litter is abrasive on silage handling equipment.

Sealing the broiler litter stack with 6 mil polyethylene to exclude oxygen is the least expensive method of heat control. Polyethylene should be used if the stack is under a barn or if it is outside. Figure 1 shows the temperature profile of two stacks of litter 12 feet deep, one uncovered and the other covered with polyethylene. To destroy pathogens in the litter, the temperature should reach 130 degrees F. If the temperature is 160 degrees F or higher, the protein becomes bound and digestibility decreases. In both stacks of litter, the temperature was in excess of 130 degrees F for 21 days. The litter covered with polyethylene achieved a temperature high enough to eliminate pathogens but did not overheat and decrease nitrogen digestibility. The litter stack that was not covered reached a temperature 27 degrees F higher than the covered stack.

Suggested Rations

Because the nutrient levels in broiler litter are variable, the suggested rations in Table 2 should be used only as a guide. A supplement of vitamin A should be added to all broiler litter rations because litter is almost totally devoid of this nutrient. Adding an ionophore such as Bovatec or Rumensin will decrease the incidence of bloat when feeding stockers.

In Table 2, Ration 1 is calculated for use as the major ration for dry beef cows until 3 to 4 weeks before calving. Hay or some other roughage should be provided to maintain normal rumen function. Approximately 5 pounds per day of long hay should be adequate. A 1,000-pound dry cow will require 20 to 24 pounds of Ration 1 during the winter months for maintenance. Corn that is mixed with broiler litter should be cracked or ground. Cattle that are fed mixtures of litter and whole grain corn or other grains tend to waste more feed than when fed ground grain mixtures due to sifting for the large kernels.

Ration 2 is formulated for the lactating brood cow. Fed at about 25 pounds daily, this ration will furnish adequate nutrients during the winter months. Some long hay or other roughage will be needed for both the lactating brood cow and the dry cow for normal rumen function.

Ration 3 is formulated for growing stocker cattle. Stocker cattle weighing 500 pounds will consume about 3 percent of their body weight of this ration. Healthy stocker cattle that have been wormed, vaccinated, implanted, and otherwise managed as recommended should gain an average of 2 pounds daily when fed this ration.

Several studies have been conducted to evaluate various feed combinations and sources of roughages for feeding stocker calves. In summary, these studies showed that feeding some additional roughage to stocker calves consuming the broiler litter mix was necessary. Feeding the roughage in a free-choice manner resulted in an increase in daily gains of .25 pounds per day over those that were limit-fed at a level of .5 percent of body weight per day (i.e., a half pound of hay per 100 pounds of body weight). In addition to cracked corn, other feeds have given similar results when mixed with broiler litter. Studies have shown that all of the corn can be replaced with soybean hulls with equal results. Another common ingredient to use is hominy feed, which is a corn product that is already ground.

Feeding Ration 3 to stockers during the conditioning period and during the typical winter deficit grazing period has been shown to improve total gain. Research has also demonstrated that stocking rates can be increased and rates of gain maintained by feeding the ration free- choice on winter grazing crops. Stockering cattle on summer pasture alone has produced only 1 pound daily gain. Providing Ration 3 free-choice increased the rate of gain to more than 2 pounds daily and increased the total pounds of beef produced. So, supplementing both winter and summer grazing for stocker cattle with the broiler litter ration results in an increased economic return.

Since only about one third of the broiler litter presently produced in the state is high enough in quality to be fed to beef cattle, all litter that is fed should be tested for nutrient content. Beef producers should use broiler litter that is at least 18 percent crude protein and is less than 28 percent ash. Not more than 25 percent of the crude protein should be bound or insoluble. Other nutrient levels are important also, but these are the most critical measures of quality. The nutrient content of broiler litter can be determined by submitting a sample through the Feed and Forage Analysis Program, Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University. Your local Extension office can provide information and materials for submitting a sample for analysis.

Conclusion

Broiler litter has been used as a cattle feed ingredient for several years without harmful effects to humans who have consumed products from these animals. The purpose of this publication is neither to promote nor to condemn the feeding of litter, but rather to serve as a source of information on using litter as a feed ingredient.

Due to the unique ability of ruminant animals to digest forages, other fibrous materials, and inorganic nitrogen such as urea, there is a growing awareness worldwide that by-products of agriculture and the food processing industry can serve as low-cost, alternative feed sources for these animals. The use of broiler litter as an alternative feedstuff may become more widespread as the need for economy in agriculture and for responsible waste management becomes more urgent.

Download a PDF of Feeding Broiler Litter to Beef Cattle, ANR-0557.

baskervillealowely.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/beef/feeding-broiler-litter-to-beef-cattle/

Post a Comment for "Analysis of Feed Grade Chicken Litter"